The Long Lineage of Russophobia

STEFAN KORINTH, 5. Juni 2023, 0 Kommentare, PDFNote: This article ist also available in German.

“The only truth emerging from Russia is lies.”

Robert Habeck, German Minister of Economics (2022)

“What is the peace that exists under Russian occupation, worrying every day that you will be murdered in cold blood, raped or even abducted as a child?”

Annalena Baerbock, German Minister for Foreign Affairs (2023)

Western politicians and journalists that speak or write publicly about Russia often do so in an almost exclusively negative and often highly deprecatory manner. Their remarks are often characterized by malicious insinuations, and any understanding of the Russian perspective is conspicuously absent. Statements by Russian politicians and journalists are consistently regarded as propaganda and lies. The Russian president is openly and blatantly insulted and equated with some of the most evil figures in world history. Russian soldiers are portrayed exclusively as war criminals, looters or rapists; Russian journalists as devious infowarriors; Russian entrepreneurs as criminals; civil servants as corrupt; indeed, the entire population of the country is depicted as more or less authoritarian, homophobic and backward.

The Western sources of these statements, on the other hand, experience almost no public criticism in their home countries. It is apparently a matter of course in the established political-media landscape that Russia may be criticized and portrayed in a way that is hardly imaginable in public relations with other countries – even those at war. In doing so, those responsible fall back on fixed thought patterns and negative images of Russia that have been repeated in Western countries for centuries, and that are merely undergoing conceptual updates. Through constant repetition, these images of Russia have become a basic truth in the West that is rarely questioned.

This phenomenon is referred to as Russophobia.

Fear, loathing, hatred

The English term “Russophobia” was coined in Great Britain at the beginning of the 19th century, when, after Napoleon’s demise, the country’s politicians and leading media positioned Russia in the public consciousness as a new, dangerous adversary of the Empire. This phenomenon was not new at the time; it was simply that a concise term for it was coined. The term Russophobia was centered on fear – fear of Russian expansion into the zones of influence of the British Empire, in Iran or India, for example. This “Russian scare” assumed such vast proportions that even the remote island nation of New Zealand built a series of coastal forts in the 1880s to ward off a perceived Russian attack.

The phenomenon of Russophobia, however, encompasses not only fear, but also has elements of prejudice and distrust and a hostile attitude toward Russia. In German, the terms Russlandhass (“Russo-hate”) or Russenfeindlichkeit (“Russo-hostility”) are sometimes used. These terms refer to “a negative attitude toward Russia, the Russians or Russian culture,” according to the discreet definition in the German Wikipedia. While no variant of the terms appear in the Duden (the prescriptive German dictionary), the Collins English Dictionary clearly states that Russophobia is “an intense and often irrational hatred for Russia.”

The historian Oleg Nemensky criticizes these definitions as trivial. Nemensky, a researcher at the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, took a more in-depth look at the phenomenon in a 2013 essay. Although hostile attitudes have survived everywhere in history and against numerous countries and peoples, he writes, Russophobia goes much further. According to Nemensky, it is an almost holistic ideology:

“[It is] a particular complex of ideas and concepts that has its own structure, conceptual system, and history of emergence and development in Western culture, as well as its typical manifestations. The closest counterpart to such an ideology is anti-Semitism.”

This parallel was also noted by the Swiss journalist and politician Guy Mettan. Mettan published a book on Russophobia in 2017 (1) in which he emphasizes the purely Western character of the phenomenon, and which does not exist in other parts of the world. Russophobia is deeply rooted in people’s subconscious in the Western hemisphere and is virtually part of the local identity, which needs Russia as an opponent in order to reassure itself of its assumed superiority.

Centuries of negative Russian portrayal

There is disagreement about when in history this attitude arose. Journalist Dominic Basulto, who sees Russophobia primarily as a media phenomenon, described in his book Russophobia (2015) how Western narratives about Russia have existed for more than 150 years. The phenomenon is “cyclical,” where narratives of a good Russia appear when Russia is experiencing a phase of weakness, while stories of evil Russia come to the fore in the Western media when the country becomes more “assertive.” These narratives are de facto timeless and almost mythological in content. (2)

Oleg Nemensky goes back even further and argues that the ideology of Russophobia emerged as early as the late 16th century, when Russians were proclaimed enemies of European Christianity alongside the approaching Turks. Russia fought several European powers in the long Livonian War (1558–1583), including Poland, Lithuania, Denmark and Sweden. The Polish nobility, who pursued territorial conquests in Russia, played the main role in the ideological justification of the war in the West and thus shaped the image of Russia.

Austrian historian Hannes Hofbauer recalls in his book Feindbild Russland. Geschichte einer Dämonisierung (Russia the Enemy: A History of Demonization) how Poland and Russia had already fought five wars over Livonia in the previous hundred years. “The image of an ‘Asiatic, barbaric Russia,’ widespread in the West of the continent, is grounded in this epoch.” (3) It arose through political interests and was the brainchild of Polish intellectuals, including the philosopher John of Glogów, the bishop Erasmus Ciolek and the University of Kraków rector John Sacranus, who spread their anti-Russian war propaganda in speeches and on pamphlets in several languages throughout Europe.

Guy Mettan, in his book, ultimately also goes back to the schism in the Christian church between the Eastern Orthodox and the Western Roman Catholic churches (the “Schism of 1054”) as the foundation of anti-Russian hostility. At that time, a fundamental conflict between East and West had already been created through propaganda and the Catholics had assigned negative attributes to the Byzantine Eastern Church and the Orthodox faithful. These attributions already strongly resembled the later Russophobic stereotypes of barbarism, backwardness and despotism.

Hostile images of Russia thus emerged in different parts of the contemporary West at different times and for different reasons. Although the background was always power politics, the justifications differed. In the Catholic Church, Russophobia was religiously legitimized; in Poland-Lithuania, it was the result of direct territorial conflicts; in the Enlightenment Age of France, it was philosophically motivated; in England, the “Great Game” meant it was imperially-driven; in post-1900 Germany, it was deep racism; and in the United States, the Cold War meant it was primarily anti-communist. These various lines of development and sources of Russophobia either remained latent or were quite open over the different periods of time, and ultimately merged into an all-encompassing, unique and very powerful phenomenon in the politically and medially united West that manifests today.

Russophobia makes use of several recurring stereotypes, which some authors also refer to as metanarratives, and it is worthwhile taking a closer look at these classic Russophobic claims that expose the deep roots and persistence of the negative Western image of Russia.

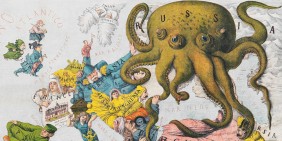

Thirst for land as an end in itself

When current German Chancellor Olaf Scholz accuses the Russian leadership of wanting to build an empire by invading Ukraine, he is treading very old Russophobic paths:

“Poland was but a breakfast … Where will they dine?” was the suspicion of the British politician and writer Edmund Burke in 1772 about Russia’s role in the first partition of Poland. (4) “When Russia has established herself on the Bosphorus, she will conquer Rome and Marseilles equally rapidly,” anticipated the French newspaper Le Spectateur de Dijon in 1854, just before the Crimean War. (5) “The future belongs to Russia, which grows and grows and lays itself upon us as an ever heavier nightmare,” was the opinion of the German Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg in 1914, shortly before the start of the First World War. The Cold War’s domino theory also fits this pattern.

For centuries, many in the Western public sphere have accused Russia’s leaders of permanently wanting to expand their sphere of domination at the expense of neighboring states. Although Russian conquests of this nature have occurred several times in history, this narrative completely ignores contrary historical developments. The peaceful withdrawal of the Red Army and the dissolution of the Warsaw Treaty after 1990, for example, had no lasting impact on the Western image of Russia; they were merely perceived as a sign of momentary Russian weakness.

Comparisons with Western countries are also revealing. The U.S. appropriated large parts of its territory through annexations and has continued to expand its sphere of influence to its current global military presence. NATO, too, has been in continuous expansion mode since its founding and today is a direct neighbor on the Russian border. For centuries, European colonial powers conquered, divided and appropriated the wealth of almost every region in the world. But none of these actions transformed their respective states into “voracious” and “hungry” empires in their own Western self-image.

The stereotype of the undying Russian thirst for land, on the other hand, is a mainstay of Russophobia and is partly based on a forged but very powerful document. According to the English historian Orlando Figes, various Polish, Hungarian and Ukrainian authors forged a will of Peter the Great in the course of the 18th century and then circulated it within Europe. The forged document, which was submitted to the archives of the French Foreign Ministry in the 1760s, spoke of an extensive Russian plan for the subjugation of Europe, the Middle East and as far as the Southeast Asia. Although the supposed Tsar’s will was recognized as a forgery from an early stage, it was instrumentalized by Western foreign policymakers as a justification for war against Russia for about 200 years. Orlando Figes writes (6):

“The ‘will’ was published by the French in 1812 – the year of their invasion of Russia – and henceforth it was reproduced and quoted throughout Europe as conclusive proof of Russia’s expansionist foreign policy. It was republished before every war Russia was involved in on the European continent – in 1854, 1878, 1914, and 1941 – and during the Cold War it was used to explain the aggressive intentions of the Soviet Union.”

Today’s insinuations that Russia would “carry on” with other Eastern European states after a victory in Ukraine also reflect the spirit of the forged will, according to criticism from the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in 2022. The fact that the will is a forgery has always been irrelevant to Russophobes, because it ideologically fits the stereotypical image: “Because, after all, forgery characterizes Russia’s policy better than any historically authenticated truth,” according to the German war propaganda concerning the document in 1916. Adolf Hitler made very similar remarks in 1941 – even though it was the German army that was stationed in Russia and annexed large territories during both world wars.

The stereotype mainly reveals the projections of the politicians of Western powers, who assign their own way of thinking and acting to the Russian leadership. Moreover, the Western refusal to accept any other reasons for Russian armed conflict than a simple lust for conquest and a primitive thirst for land, which still prevails today, is a central reason for the intellectually extremely limited conflict analyses that are prevalent in the West with regard to the current war. Politicians and journalists who cannot imagine that – rather than wanting to rebuild the Soviet Union – the Russian invasion of Ukraine serves to prevent an existential NATO threat to Russia’s heartland, counteracts any constructive problem-solving and instead promotes the making of very dangerous politico-military decisions.

A country of barbarians

Another centuries-old constant of Russophobia is the conviction that Russia is backward and, at its core, savage and uncivilized to the point of barbarism. This stereotype is applied to Russia’s degree of material and technological development as well as to the intellectual and cultural makeup of its population. A regular parallel to this assertion is an obvious Western sense of superiority and the belief that Russia must first catch up with what the West has long since achieved.

This belief is perceptible in very different public discourses, whether about Russian social policy, economics and technology, or the current war. If we restrict our view to the topic of the war, we already see numerous echoes of this stereotypical image of Russia: Western politicians and journalists have accused Vladimir Putin of acting like a “19th century ruler” in the Ukraine conflict. One can regularly read of the Russian army possessing “outdated weapons” and that, without the import of advanced Western technology, their arms industry is facing rapid collapse. In addition, Russia is traditionally fighting this war using mass rather than class, acting according to “obsolete doctrines”; the Russian army – in contrast to NATO – is even so unprofessional and barbaric that, apart from war crimes, it is incapable of getting anything done.

The stereotype of Russian backwardness is ancient and could historically only have taken root because contrary facts were consistently ignored in the West. “Russia is like another world,” wrote Bishop Matvey of Kraków as early as the mid-12th century in a letter to the French crusading preacher Bernard of Clairvaux. But the stereotype did not really catch on until the transition from the Middle Ages to modern times, when Europe began to form an identity as a separate cultural area, which was essentially achieved by distinguishing itself from other cultural areas, explains historian Christophe von Werdt.

“Russia played a particularly important role in this interplay of European identity formation and perception of what was foreign. For in its case, Europe was confronted with a ‘foreign’ Christian land that it could not colonize or culturally assimilate.”

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Western Europeans increasingly came to Russia as diplomats, mercenaries or merchants, recording their impressions of the unfamiliar country. Eastern European historian Manfred Hildermeier writes that the cultural distance evident in the records was “increasingly combined with a sense of superiority.” German travelers, for example, reported with amazement that Russians bathed naked in the river in full view of others and men and women were not separated by gender in the saunas located almost everywhere, but went there together. The public blowing of noses, spitting, belching or swearing were viewed with outrage by Western visitors at the time.

“What travelers denounced about Russia was not least the past of their own culture. This may also explain the superiority they assumed towards themselves and clarify why they overlooked what did not fit into their image – for example, the frequent sauna visits of the Russians (at a time when perfume replaced washing in European aristocratic courts), the frowning upon of the display of nudity … or the fact that no Russian was waving a sword (if only because he did not carry one) and no blood flowed from the loud bickering. The travelers did not succumb to any misunderstanding, but were partially blind.” (7)

The Swiss author Guy Mettan demonstrates the selectivity of Western judgment even more pointedly. He compares the popular 1761 travelogue of French astronomer Jean Chappe d’Auteroche with the contemporaneous account of a Japanese boat captain named Kodayu, who traveled the same route through Siberia at the same time as the Frenchman. “But they seem to describe two different planets,” notes Mettan (8); the accounts of their voyages could not be more different.

Whereas d’Auteroche discerned backwardness and barbarism everywhere in Russia, Kodayu soberly describes everyday life, living conditions and socio-political circumstances. Reading both books side by side is fascinating, because it painfully reveals the contrast between the impartiality of the traveler from the Far East and the Westerner’s urge to judge others from a position of superiority and emphasize his supposed civilizational advantage.

It can be equally argued that from the perspective of other regions in the world, Russia was specifically not underdeveloped or uncivilized. Manfred Hildermeier explains: “Those who attested to the Russian Empire’s backwardness measured it [exclusively] by the Western European yardstick.” (9) Western Europeans had always located progressiveness only in themselves. Hildermeier, a historian of Eastern Europe, considers the stereotype of backwardness so central that he devoted the entire final chapter of his book Geschichte Russlands (History of Russia) to it.

Certain Russian intellectuals and some of the Russian upper class also contributed to the consolidation of the concept by adopting it and declaring some countries in the West (the Netherlands, France, Italy, Prussia) to be models in certain fields of knowledge that should be emulated. The most famous example is certainly Peter the Great, who “whipped” Russia into the European modern era with numerous reforms from above after his European tour.

Hildermeier writes, however, that backwardness is always relative, or rather, temporary and limited to certain areas. In other words, once a country has caught up in one sector, it could always become a leader in that field. Russian achievements in the natural sciences and arts in the 19th century or in aeronautics and space travel in the 20th century are examples of this. Russia also shifted from simply transplanting Western innovations under Peter the Great to creatively and innovatively adapting these models to its own conditions in subsequent centuries – because they needed to function there.

Due to its geographic expanse, Russia is characterized by large discrepancies between the various parts of the country, which is why it can hardly be compared with countries like France, England or Germany, and can thus only adopt their supposedly successful models to a limited extent. What do you focus on? On the provincial village or the vast metropolis? On the eve of the First World War, St. Petersburg and Moscow were mentioned in the same breath as Berlin, Paris and London, Hildermeier argues. And which specific sphere should one consider? After Alexander II’s judicial reforms, Russian judges enjoyed “an independence that was unparalleled in Europe.” (10)

But for centuries, Western politicians and journalists have rarely bothered with such differentiations. It was not Pushkin, Gogol, Tolstoy or Tchaikovsky who exemplified Russian culture, but often instead the fleas and lice. The early stereotype of backwardness and barbarism of the Russians, once created by Western European visitors, has remained stubbornly intact over the centuries. While it has been conceptually updated here and there, at its core the prevailing pejorative judgments are undifferentiated to this day:

Adam Olearius, German Visitor to Russia (1656):

“If one considers the Russians according to their dispositions/customs and life / they are to be counted among the barbarians … being guileful/stubborn/ unbending/repugnant/perverse and unashamedly inclined to all evil.”

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, French Foreign Minister (1796 to 1807):

“The whole system [of the Russian Empire] … is calculated to swamp Europe with a flood of barbarians.” (11)

George S. Patton, U.S. general (1945):

“In addition to his other Asiatic characteristics, the Russian has no respect for human life and is an absolute son of a bitch, barbarian and chronic drunkard.”

The German daily paper BZ (2022):

“They loot, rape and torture: this is how Putin created his barbarian army.”

Of course, there has always been propaganda of atrocity and a devaluation of the enemy in times of war, but towards Russia this disparaging view prevails almost permanently in the West. None of the above quotes were made by people who were at war with Russia; the stereotype of barbaric, uncivilized Russia seems to be unshakable.

"Barbarism and Cholera Enter Europe," lithograph by Auguste Raffet on the Russian suppression of the Polish November Uprising in 1831 | Source

Since this model of thinking has become a kind of unquestioned truth in the West, events such as the so-called Sputnik crisis (1957), when the supposedly backward Soviet Union surprisingly sent the first satellite into space, will inevitably occur at some point. In his autobiography, French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann recounts how he learned from his host at a 1961 high society dinner that a Russian had just become the first man to fly into space. Georges Pompidou, who would later become the French Prime Minister and President, and was seated next to Lanzmann, refused to believe this and simply replied, “That is propaganda!” (12)

The eternal Russian lie

The craftiness and deceitfulness of Russians is another recurring paradigm of Russophobia. As early as the 16th and 17th centuries, Western visitors to Russia identified deceitfulness and mendacity as typical Russian character traits – not, however, as traits of individual Russians, but of all Russians. According to Russophobic logic, this general character trait, by association, will then also be reflected in Russian politics.

Accordingly, numerous claims that Russia always employs deceit and lies in foreign policy are documented for the following centuries. “Russian diplomacy, as you know, is one long and manifold lie,” claimed British statesman George Curzon in 1903, for example. (13) Allegations of this sort extend to present-day accusations that Russia permanently employs propaganda and manipulates Western elections.

“In times of peace, Russia strives to force not only her neighbors but all the countries of the world into a state of confusion through distrust, turmoil and discord. … Russia is not moving directly toward its goal … but is undermining the foundations in the most devious way.” (14)

This statement about a form of hybrid Russian warfare sounds quite familiar to the ears of today’s media users, but it is already more than 200 years old and comes from the French diplomat Alexandre d’Hauterive during the time of Napoleon Bonaparte. Writing about the English media during the Great Game, historian Orlando Figes notes:

“The stereotype of Russia that emerged from these extravagant writings was that of a brutal power, aggressive and expansionist by nature, but also sufficiently devious and deceitful to conspire with ‘invisible forces’ against the West and infiltrate other societies.”

Modern assertions of this nature sound something like this from the German Federal Academy for Security Policy (2017):

“In its war against the West, Russia resorts to a variety of tools. A number of state-controlled media (at home and abroad) are used for propaganda purposes – with the aim of undermining the trust of Western societies in their own institutions and political elites. … In its confrontation with the West, Russia is using methods that in the past were primarily used against former Soviet states (so-called near abroad) or non-Western states. This is especially true of aggressive cyberattacks combined with massive propaganda aimed at interfering in internal affairs and influencing political processes.”

At this point, there is no need to discuss the blatant double standards of such analyses, which simply forget the countless Western-organized election interference, coups, cyberattacks and other hybrid destabilization attempts in countries around the world. What then becomes clear is that despite their different ages, the Russophobic claims cited are nearly identical and are interchangeable. And like the stereotype of the Russian thirst for land, this cliché also primarily highlights the projections of Western politicians and journalists. This logic becomes particularly clear when looking at the period from 1917 to 1919.

After Lenin had been smuggled into Russia by the German rulers and led the successful Bolshevik Revolution, the German rulers began fearing a similar occurrence of this Russian experience in their own country, explains historian Mark Jones. In January 1919, German newspapers of nearly every political shade alleged that Russians were instrumental in the Spartacist uprising in Berlin and the calling for an armed struggle against Germany.

“This propaganda was widely believed and led to an increase in xenophobia as early as the founding phase of the Weimar Republic, which later escalated further in the Third Reich. In fact, none of it was true.” (15)

Jones further explains that many politicians and journalists believed that a large amount of Russian money was flowing into Berlin to finance the uprising. Russophobic sentiment in the media had bloody consequences: Government troops committed numerous atrocities during the crushing of the Munich Soviet Republic in May 1919. The largest single incident of this kind was the shooting of 53 Russian prisoners of war on May 2 in Gräfelfing – under the accusation that the Russians had fought for the Soviet Republic.

The stereotype of Russian intrigues and lies appears on many thematic levels. The devaluation of every opposing Russian position as “propaganda” and “lies” is a core component of Russophobia, writes Dominic Basulto in his book. Thus, a country whose leadership always lies cannot have a state media that legitimately disseminates its own government’s perspectives abroad, as the state media of other countries do. No, in the eyes of Russophobes, Russian state broadcasters must necessarily always be “propaganda broadcasters.”

Western observers have been indignant about the European-like appearance of Russians for centuries, meaning the Russians, in their clothes and appearance, are virtually lying already. The French writer Astolphe Marquis de Custine wrote in 1839:

“I do not reproach the Russians for being what they are; what I reproach them for is pretending to be what we are. They are still uncultured … and in this they follow the example of the apes and disfigure what they copy.”

That the Russians “ape” French culture was also reported in French newspapers in the run-up to the Crimean War. And this is where the Russophobic clichés collide. If the Russians try to remedy their supposed backwardness by orienting themselves toward the West, then they are wrong again; at heart, they remain half-savage barbarians.

Russians are people “with a Caucasian body and a Mongolian soul,” wrote the U.S. journalist Ambrose Bierce in his “Dictionary of the Devil” in 1911. (16) Bierce meant this satirically – as he did with each of the approximately 1,000 entries in his book. He critically echoed the clichéd thinking of his time. In 2022, the political scientist Florence Gaub told ZDF, a German public television broadcaster: “We must not forget that even if Russians look European, they are not Europeans, in this case in a cultural sense.” She did not mean this satirically.

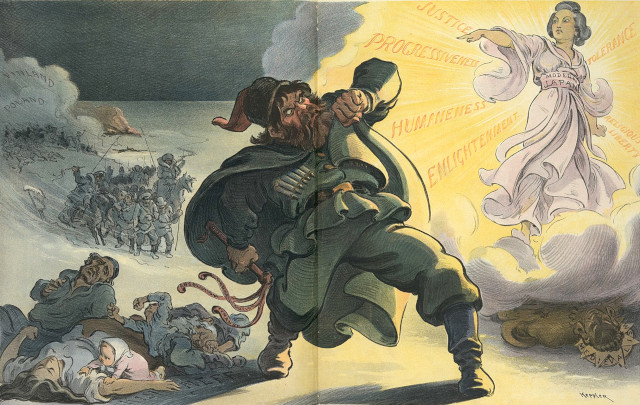

The despot and his obedient nation

Probably the most powerful element in Russophobia is the stereotype of Russian tyranny. It entails two complementary parts: a demonic leader and a sort of slave mentality of the Russian population.

Tsar Ivan IV – in Russian he is called “the Austere,” while in the West he is called “the Terrible” – was an archetype of the cruel Russian ruler, explains Oleg Nemensky. According to Nemensky, the “black myth” of the bloodthirsty tyrant, “whose brutality allegedly exceeded all conceivable limits,” emerged in the 16th century at the time of the Livonian War and occupied the most important place among the propagandistic Russian stereotypes of the time. Ivan the Terrible, in Western eyes, “combined the symbolization of evil and brutal power with the servile bondage of his subjects.”

Indeed, Ivan IV was a brutal ruler and apparently a sadistic character who employed cruel methods of torture and execution. However, whether this made him exceptional in his time is questionable. Yet, Ivan the Terrible’s legendary reputation established the image of Russian rulers in general in the rest of Europe, which was also basically applied to the Russian rulers of the following centuries: cruel, tyrannical, brutal. The fact that soon after the 31-year reign of Ivan, Tsar Alexei I, who bore the epithet “the meekest,” on the other hand, is something few will ever have heard.

We will not quote here all the insults that Western voices have used to describe the Russian leaders in office. From calling Tsar Peter I the “greatest barbarian of mankind” (Montesquieu) to dubbing Vladimir Putin a “killer” (Joe Biden), this centuries-long list would be quite extensive.

Undoubtedly, it is common in wartime to demonize the leader of an opposing power as personified evil. According to Arthur Ponsonby, it is one of the tenets of wartime propaganda to direct hatred at the enemy leader. But in the Russophobic culture of many Western countries, this logic also applies in peacetime. Although exceptions can be found of Russian leaders who were at times viewed positively in the West because they had achieved extraordinary things – Alexander I (victory over Napoleon) or Mikhail Gorbachev (German reunification) should be mentioned here – as a rule, the opposite is true.

For example, the fact that Vladimir Putin was to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Hamburg in 2004 caused such indignation in parts of the public that both the university and Putin decided against it. The reason for the storm of protest, it was reported, was the “Chechen war waged in a manner contrary to international law.” In 2011, the planned awarding of the Quadriga Prize to Putin (then the Russian prime minister) was also cancelled due to general outrage. In contrast, these standards were not applied to U.S. presidents: Bill Clinton, who shortly before had commanded a war of aggression against Yugoslavia in violation of international law, received the German Media Prize in 1999, the Charlemagne Prize in Aachen in 2000 and the European Mittelstandspreis (Medium-Sized Business Prize) in 2002.

According to Dominic Basulto, the comparison of these two presidencies is wholly relevant to the analysis of Russophobia because the Western media regularly portray the leaders of Russia and the U.S. as if they were direct opposites. The Russian leader, he says, always plays the role of the “dark twin.” This has culminated in the centuries-old depiction of Russia as “the other,” “the evil.” In Western eyes, there has always been this dualism between us and them, freedom and tyranny, democracy and autocracy, civilization and barbarism, light and darkness. The media-political portrayal of Russia as the “evil empire” (Ronald Reagan) is often downright cartoonish.

“The yellow peril,” caricature by Udo Keppler, 1904 | Source

Oleg Nemensky explains how this Manichean worldview is particularly characteristic of contemporary American culture and implies the existence of absolute good, embodied by the U.S., and absolute evil. “The Cold War years established Russia in this position,” and to this day, he says, nothing has changed. Incidentally, the U.S. adopted many aspects of its Russophobia from the British Empire. Nemensky emphasizes that it is extremely remarkable that the antithesis of Western freedom vs. Russian slavery is reproduced again and again across different eras of history, even if there is a change in the specific concepts. No role is played by the centuries of Western slavery, which lasted even longer in the U.S. than serfdom did in “backward” Russia.

According to the Russophobic narrative, Russians are a people incapable of governing themselves and therefore covet slavery. A people that is consistently ruled by tyrants and dictators must itself be inherently authoritarian and subservient, according to the circular argument that has been recapitulated for centuries.

“This nation finds more pleasure in slavery than in freedom,” the Austrian envoy Sigismund von Herberstein reported from Moscow in 1549. The Russians are a “tribe born into slavery, accustomed to the yoke and unable to bear freedom,” the Dutchman Edo Neuhusius told his readers in 1633. (17) “Political obedience has become a cult, a religion for the Russians,” the abovementioned Astolphe Marquis de Custine noted in 1837. “Russia was for us the epitome of bondage and forced rule, a danger to our civilization,” wrote German public broadcaster ARD correspondent Fritz Pleitgen about the thinking of German journalists in the 1960s. (18) “‘Slave consciousness’: Why are many Russians so submissive?” asked the German public broadcaster Bayrischer Rundfunk in 2022.

As strikingly interchangeable as these statements are across the centuries, this insight is useful for understanding the deep-seated, traditional hatred of Russia among the liberal middle classes of Western countries. It is precisely in these groups, represented today by the Democratic Party in the U.S. or the Green Party in Germany, for example, that the stereotype of a despotic Russia has always been extremely powerful.

The Polish uprising against Russian “tyranny” in 1830/31 was an initial spark and engendered great enthusiasm among the liberal German media and the student movement, as well as in France and England. The crushing of the Polish uprising at the time went down in the history books and numerous “Poland songs” (Polenlieder) were written in Germany. The lyrics of one stated:

“We saw the Poles, they went out, as the die of fate fell. They left their homeland, their father’s house, in the barbarians’ claws: The freedom-loving Pole does not bow to the dark face of the Tsar.” (19)

At the time, the politician Friedrich von Blittersdorf recognized an “almost mysterious enchantment of governments and an equally incomprehensible delusion of many statesmen.” Parallels to the “solidarity” with Ukraine in 2022 are unmistakable.

In support of the liberation of Poland, the left in the Paulskirche parliament (the Frankfurt Parliament) also flirted with a great war against Russia in 1848. (20) According to Hannes Hofbauer, this German left at the time, which saw itself as patriotic and liberal, always viewed the tsarist empire as a threatening stronghold. Liberal intellectuals also attributed all kinds of negative characteristics to the Russians. In the course of their criticism of autocracy, German liberals developed the image of a “despicable Russian national character,” which over the decades advanced into full-blown racism against the Russians.

Friedrich Engels, who developed from a radical democrat into a communist theorist, was one of the political journalists who attributed a civilizing role to the Germans and a barbaric role to the Russians in Europe. The tsardom, he wrote in 1890, was already a threat and danger to us by “its mere passive existence,” and, moreover, that Russia’s “incessant interference in the affairs of the West is hampering and disturbing our normal development.” Marx and Engels called for revolutionary war against Russia. Their passionate struggle against the Russian monarchy “has not unjustly been called Russophobia,” wrote sociologist Maximilien Rubel. (21)

Thus, Russophobic positions also found their way into German social democracy. Anti-Russian affects were as strong in the SPD as they were in the liberal movement of Great Britain, according to historian Christopher Clark with regard to the phase before World War I. (22) The SPD leader August Bebel, who also rose through the liberal-democratic movement, said the following (23) in a 1907 speech:

“If it came to a war with Russia, which I regard as the enemy of all culture and of all the oppressed, not only in my own country, but also as the most dangerous enemy of Europe and especially for us Germans … then I, an old boy, would still be ready to take up my rifle and go to war against Russia.”

Today’s members of the German Bundestag are likely no longer prepared to offer this commitment, but their statements about Russia otherwise sound very similar.

Conclusion: The rhetorical path to war

Ten years ago, Oleg Nemensky wrote that although Russophobia is a system of views that emerged over centuries, it exists in an almost unchanged form to this day in Western countries. The phenomenon occurs in the West as a kind of “reverse political correctness,” he said. Since 2013, Russophobia has once again intensified considerably. Currently, we are dealing with a peak of Russophobic statements, which have been repeatedly delivered in the run-up to wars. The degree of Russophobia could therefore serve as an indicator for attentive observers of current events. It is particularly dangerous when politicians and journalists not only politically instrumentalize Russophobic stereotypes, but actually believe them.

It has also been observed historically that Russophobia eventually subsides. This could happen even without war, as the end of the bloc confrontation in 1990 showed. However, the phenomenon will not disappear, but will remain latent as long as Western societies do not fundamentally address the problem. Historical models exist for this, and the parallels between Russophobia and anti-Semitism are a topic in themselves. Therefore, we will not go into the corresponding proposals for solutions, such as those made by Nemensky (a UN resolution against Russophobia, the establishment of an anti-defamation league and specialized institutes that investigate and publicly denounce cases of Russophobia). We will only say this much: These proposals would be difficult to implement at present, since they would have to be supported by governments and the leading media, specifically in the West, because that is where the core of the problem lies.

Former CIA official Phil Giraldi, for example, said in an interview that the Biden cabinet is full of Russophobes who blame Russia for all sorts of things. He also said that many people in the CIA were motivated by Russophobia and believed the stereotypes. In the political-media landscape of Western countries, however, people are usually unwilling to even recognize the problem. The accusations of Russophobia are only a kind of clever distraction from Russian atrocities and are only meant to discredit Kremlin critics – as typically portrayed here in the Swiss paper, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

What is clear from all this is that the phenomenon of Russophobia has little to do with Russia and the Russians themselves – but a lot to do with Western societies. It is a permanent thinking of superiority, a deliberate double standard. Yes, Russia wages wars; Russian politicians and journalists have lied and Russian soldiers have committed crimes. Yet all these aspects apply at least as much to actors in Western countries. But while here one glosses over one’s own wars, forgets one’s own lies and reinterprets one’s own crimes as individual cases, one declares such acts with regard to Russia to be the norm that applies always and everywhere.

Russophobia is at its core a racist phenomenon, notes Guy Mettan. Russophobes fundamentally refuse to recognize people from Russia or the Russian state as equal and equivalent to their corresponding Western counterparts. People from Russia have their own life experiences and political perspectives, and their state has its own economic and political interests that are no better or worse than their counterparts in the West. The interests and the means used to achieve these could be both legitimate or illegitimate, legal or illegal, moral or immoral. This must be examined objectively in each case – but not always and from the outset condemned using centuries-old, pejorative stereotypes that lead to nothing but hatred and war.

Victor Klemperer wrote (24) directly after the Second World War:

“I want to emphasize it particularly profusely here and today. For it is so bitterly necessary for us to get to know the true spirit of the peoples from whom we have been closed for so long, about whom we have been lied to for so long. And about none have we been lied to more than about the Russian.”

Notes

(1) Guy Mettan: Creating Russophobia, Boston, 2017. Page 21 states: Like anti-Semitism, Russophobia is “not a transitory phenomenon linked to specific historical events; it exists first in the head of the one who looks, not in the victim’s alleged behavior or characteristics. Like anti-Semitism, Russophobia is a way of turning specific pseudo-facts into essential, one-dimensional values, barbarity, despotism and expansionism in the Russian case in order to justify stigmatization and ostracism.”

(2) Dominic Basulto: Russophobia. How Western Media Turns Russia Into The Enemy. 2015; page 2 f.

(3) Hannes Hofbauer: Feindbild Russland. Geschichte einer Dämonisierung (Russia the Enemy: A History of Demonization). Vienna, 2016; page 13 f.

(4) Quoted from Adam Zamoyski: 1812. Napoleons Feldzug in Russland (Napoleon's Campaign in Russia). Munich, 2004; page 37.

(5) Quoted from Orlando Figes: Krimkrieg. Der letzte Kreuzzug (Crimean War. The Last Crusade). Berlin, 2011; page 236.

(6) Quoted from Figes; page 126.

(7) Manfred Hildermeier: Geschichte Russlands. Vom Mittelalter bis zur Oktoberrevolution (History of Russia. From the Middle Ages to the October Revolution). Munich, 2013; page 380ff.

(8) Guy Mettan: Creating Russophobia, Boston, 2017. Page 155 ff.

(9) Hildermeier; page 1321.

(10) Hildermeier; page 918.

(11) Quoted from Figes; page 125.

(12) Claude Lanzmann: Der patagonische Hase. Erinnerungen (The Patagonian Hare. Memoirs). Reinbek, 2012; page 464.

(13) Christopher Clark: Die Schlafwandler. Wie Europa in den Ersten Weltkrieg zog (The Sleepwalkers. How Europe Entered the First World War). Munich, 2015; page 190.

(14) Quoted from Figes; page 125f.

(15) Mark Jones: Am Anfang war Gewalt. Die deutsche Revolution 1918/19 und der Beginn der Weimarer Republik (In the Beginning was Violence. The German Revolution 1918/19 and the Beginning of the Weimar Republic). Berlin, 2017; page 209 f. as well as page 178 and 297.

(16) Quoted from Basulto; page 16.

(17) Quoted from Nemensky; footnote 18.

(18) Fritz Pleitgen, Mikhail Shishkin: Frieden oder Krieg. Russland und der Westen – eine Annäherung (Peace or War. Russia and the West – a Rapprochement). Munich, 2019; page 20.

(19) Quoted from Hofbauer; page 33.

(20) Sebastian Haffner: Von Bismarck zu Hitler (From Bismarck to Hitler). Munich, 2001; page 11.

(21) The claim that Marx and Engels’ criticism of Russia was Russophobia is, however, debatable. Both sharply criticized the tsarist autocracy, but were also close to Russian revolutionaries and communicated extensively with them. Engels learned Russian as a young man; Marx was trying to acquire the language in his old age.

(22) Clark; page 673.

(23) Quoted from Hofbauer; page 37.

(24) Victor Klemperer: LTI. Notizbuch eines Philologen (LTI – Lingua Tertii Imperii. The Language of the Third Reich. Notebook of a Philologist). Ditzingen, 2010; page 179.

Diskussion

0 Kommentare